A Geekist Exploration of What Powers the Tools That Power Us

Ever wondered how modern tooling just works™?

In this post, we’ll explore the engine rooms behind the frameworks we lean on every day, and hopefully you’ll walk away with a clearer sense of the machinery hidden beneath the hood.

→ collecting fragments… → builder queue primed… ● unexpected prose divergence… ← rollback triggered… → resuming author in safe mode…

Anyway… where were we?

Ah yes, tooling.

Every tool we use behaves as if there’s a small, overworked concierge living inside it.

Doesn’t it? It’s like Charon in John Wick: impeccable service, absolute discretion, but if you mess up the config, you’re on your own. And no one is going to watch your dog.

You run build, and everything obediently runs

- TypeScript becomes JavaScript (that no one wants to read).

- Sass becomes CSS.

- Markdown transforms into HTML.

But we rarely pause to ask the only question that actually matters:

How does the tool know what to do first?

Under the hood, something knows that the eggs get cracked before they get beaten… what must wait for the pan to heat, and what absolutely cannot be trusted unsupervised.

That organising instinct is the heart of tooling, the thing most developers never look at because everything “just works” …until the day it doesn’t – at which point we’re staring into a screen lit up red, frantically searching StackOverflow to see whether anyone else has suffered the same catastrophe.

But the secret is that all of these tools – and that’s regardless of branding, attitude, or celebrity endorsement – share a single machinery type.

They all run on pipelines.

If you prefer industry labels, there are plenty.

ETL. Compiler passes. Cloud functions in a daisy chain. CI pipelines. Data pipelines. Build pipelines. Delivery pipelines.

Every one of them is a different costume placed on the same underlying idea: a line of responsibilities, executed in order, passing artefacts forward.

Once you start paying attention, you’ll see this structure everywhere. Webpack’s chaotic reputation hides a surprisingly strict internal order. Next.js feels effortless because every part of it knows exactly when it’s allowed to run. Nx organises its world like someone colour-coding their entire life. Even the slightly smug modern tools (Astro comes to mind) depend on that exact same pattern.

So what exactly is a pipeline?

If you strip the utility (and perhaps the branding) away, what you’re left with is something surprisingly humble. A pipeline is nothing more than an agreement.

A promise, really, that certain things happen before others. That’s it. That’s the whole magic trick. One step produces something. The next step consumes it. And the next one, and the next one, until you end up with something vaguely resembling the thing you asked for in the first place.

A pipeline is the developer equivalent of mise en place. Everything has its place on the counter. Everything has a time when it enters the scene.

Somewhere in the early chaos of build tooling, engineers probably realised that letting everything “just run whenever” was tantamount to a suicide pact. So the industry, in its infinite wisdom, invented the simplest salvation imaginable: “What if… we ran things… in order?” The fact that this worked, and continues to work, is a testament to how little we actually need.

Because once you see one (or build one), it becomes almost laughably honest. It has no ego, no theatrics, and certainly no aspiring illusion of being an AI-powered mastermind.

It just walks down a list, tapping each little worker on the shoulder as if to say, “Your turn.” Some workers return tiny gifts. Others return fully formed artefacts. Some return nonsense. Some throw errors because they weren’t prepared, or they didn’t get the thing they were supposed to get, or they looked at your config and decided they refused to participate in this farce.

The pipeline keeps going anyway. It doesn’t complain. It just does the work, probably a little resentful if it could feel anything at all.

But they aren’t rigid. They’re not mechanical in the “factory in 1905” sense. They’re structured, yes, but they can be expressive. They can branch, converge, or negotiate. They can inspect their own state. They can retry. They can roll back. They can gossip about the work they’ve just done. They can whisper diagnostics into your console like a confessional booth for code.

Heck, if you’d like they can even compute the number of “Hail Mary’s” you’d need for penance.

If that sounds dramatic, it’s because modern tooling is dramatic. It’s theatre. You think you’re watching the play, but backstage there’s a frantic dance of actors hitting their marks. You only see the grace because someone else solved the panicking so you don’t have to.

Knowing this lets you reason about tools you use, and now that the curtain has been pulled back, we can get a little closer to the heart of it. Because beneath the metaphors and the choreography, a pipeline is made up of only three things:

the work to be done, the relationships between the pieces, and the direction everything flows.

It’s a map.

Let’s talk about that.

The Map, Not the Line

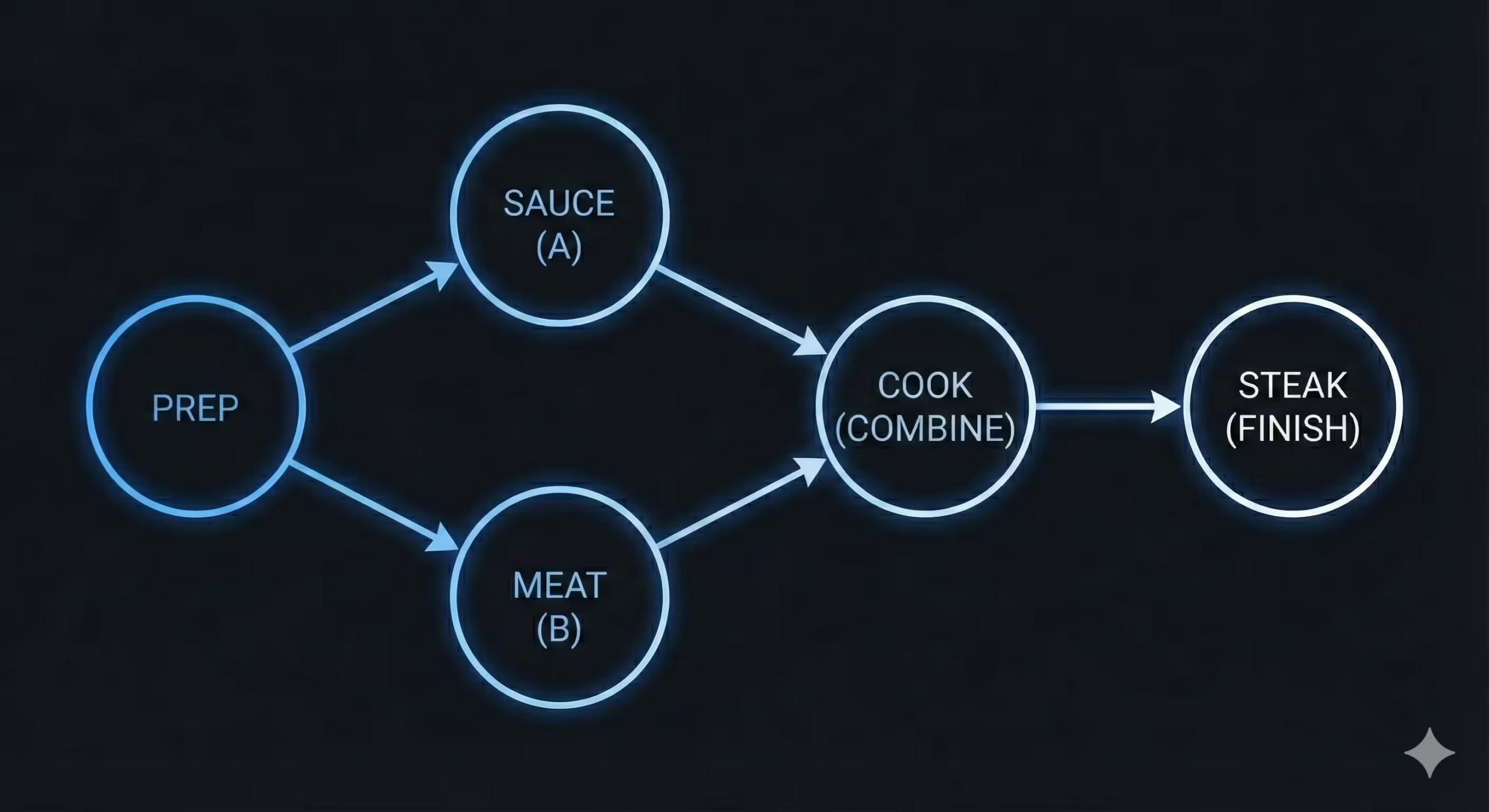

Most people picture a pipeline as a neat procession. A beginning, some middle steps, and an end. A queue of workers waiting for their turn to contribute something valid. The diagram above illustrates this intuition perfectly, and yet it still undersells what’s really happening.

Because the real question isn’t what happens first.

The real question is what decides what happens first.

What chooses whether you make the sauce before the meat? Or whether both can proceed independently? What decides when they’re allowed to meet in the pan?

Unlike cooking though, where the chef would probably get away with a misstep by calling it culinary improvisation, code needs something that resembles the laws of physics to get things right. Don’t panic. That too was a metaphor.

Below the friendly surface of “run build” lives a system where every action is spatial, not sequential. Sauce and Meat don’t care about each other until the moment they absolutely have to. Prep doesn’t care about Cooking. Cooking can’t begin without both its dependencies completed in the correct order, with the correct output, and in the correct state.

Yep. Well-done vs Medium-rare are both still states.

Nothing moves until the things it depends on are done. Not because someone told it to wait, but because, in this little universe, waiting is the only possible choice.

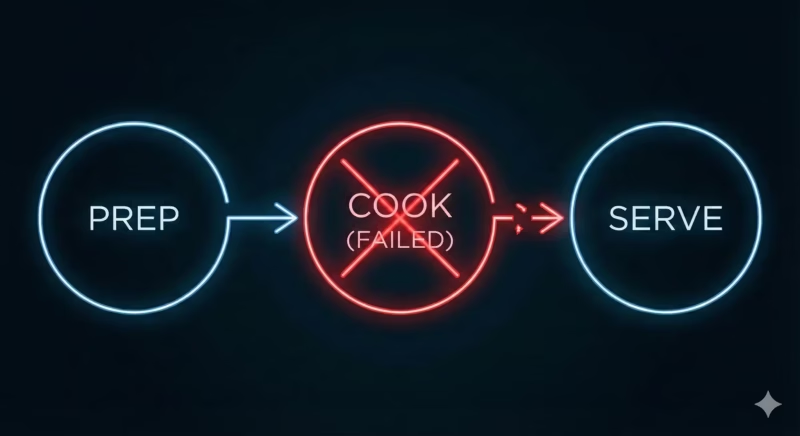

And that’s all well and good when everyone behaves. When the sauce is punctual, the meat is compliant, and the pan isn’t having an existential crisis. But the universe has opinions, and so do build steps.

Which brings us to the inevitable moment, the one every kitchen, every toolchain, and every pipeline eventually meets:

What happens when the Chef de Partie absolutely butchers the sauce?

It’s a stupidly funny question, but it’s the one that finally exposes what a pipeline really is. All that order, all that choreography, all that discipline… it lasts exactly until step(s) refuse to hold up their end of the deal.

Because here’s the reality:

a pipeline isn’t held together by sequence. It’s held together by expectations.

And when one step breaks its expectation, everything downstream loses its footing. The work can’t continue. The line doesn’t advance. The map hits a dead end.

That’s the moment the system has to make a choice. And the way it responds to that choice is what separates a reliable tool from one that wrecks your day.

Do we barrel ahead and pretend nothing happened? Or do we admit the cook burned the sauce and figure out how to get back to a state that actually makes sense?

That’s where rollbacks enter the story.

When the Map Has to Run Backwards

In the physical world, mistakes are usually permanent. You cannot un-crack an egg. You certainly cannot un-send that email to the entire company distribution list.

But inside the pipeline? Time is negotiable.

A rollback is the tool’s way of admitting defeat with dignity. It is the digital equivalent of a magician failing a card trick, pausing, and suddenly holding a brand new deck as if nothing happened.

It relies on a concept that database engineers have worshipped for decades, and frontend developers are just starting to appreciate: Atomicity.

“All or nothing.”

See, a good pipeline treats a unit of work like a hostage exchange. Either everyone gets across the bridge safely, or nobody moves. If the CSS compiles but the JavaScript throws a syntax error, a good build tool doesn’t give you a half-broken site. It kills the process, scrubs the temporary files, and leaves your dist/ folder exactly how it found it.

It protects you from the “half-state” – the most dangerous place in software, the “Uncanny Valley” of code where everything looks fine until you actually try to use it. It’s when the database has the user’s new email address, but the authentication service still has the old password. It’s when the npm install finished, but the post-install script died, leaving your node_modules in a state of purgatory.

In a kitchen, (sorry for the relentless kitchen analogies but it works irresistibly well here), you simply cannot un-burn food. You throw it out, curse under your breath, and start again with clean equipment. In a pipeline, the same thing happens in a more disciplined way: a new set of steps kick in whose only job is to walk the system back to a safe place.

Rollbacks prevent the half-state. They are the custodial staff coming in to mop up the mess so the guests (your users) don’t know a dish caught fire

try {

await prepareSauce();

await cookMeat();

await plateDish();

} catch (fire) {

// The crucial step we often forget

await extinguishFire();

await apologyToCustomer();

await restoreSanity();

} This is why git is so powerful (and terrifying). It is essentially a time machine built entirely out of rollbacks. When you mess up a merge, you aren’t fixing the code; you are rewinding reality to a point before you made the bad decision.

What This Changes (Even If You Never Touch a Pipeline API)

Once pipelines, maps, DAGs, rollbacks, half-states, and time-travelled merges click into place, it’s tempting to file the whole thing under “nice theory” and get back to shipping features. But this is exactly the sort of theory that changes how tools are read, debugged, and designed.

Next time a build fails, it stops being “Vite is broken” or “Webpack hates me.” It becomes a specific node on a map refusing to deliver what everything downstream was expecting. That small reframing is often enough to move from vague frustration to concrete investigation.

When a tool offers --watch, incremental builds, or cached tasks, the promise becomes clearer too. Under the marketing, those features are all variations of the same behaviour: reuse the parts of the map whose inputs haven’t changed, and rerun only the nodes whose world has shifted.

It’s a graph with memory.

It shifts the way you think about things you do every day, from just “a bunch of shell scripts” to modelling them as steps, dependencies, expectations, and recovery paths. Some failures are acceptable and can be retried. Some demand a rollback. Some must never leave the system in a half-state. But all of them? Design choices.

So it’s not so much about the ability to drop “Directed Acyclic Graph” into casual conversation, although no one said you couldn’t, it’s the fact that the machinery is no longer an oracle; it is a system with very opinionated roads.

If You Want to Poke the Machine Itself

A developer can live an entirely productive life never once implementing a custom pipeline.

Some readers, however, prefer to see the gears.

For that purpose, there is a pipeline engine extracted into its own package: a TypeScript library originally built to drive WPKernel’s code-generation stack, but maintained as an independent module. On npm, it is marked as beta because the surrounding framework is still evolving, not because the core pipeline is a toy.

The engine in that package already does the work described in this essay: it registers helpers, builds a dependency graph, resolves order, short-circuits on errors, and coordinates rollback sequences to avoid half-states.

For anyone curious enough to inspect the internals, it starts here:

npm install @wpkernel/pipeline

We hope this shines some light into an otherwise dense topic. We deliberately stayed wide-angled with this piece to hopefully reach a larger audience, but there is much more under the surface. Registration mechanisms. The details of graph construction. How diagnostics are threaded through and cool mechanisms around sorting tasks.

Those are stories for another day.

For now, feel free to drop a comment or star the repo to stay updated!